“Water is a fascinating topic that connects the past with the future, the environment with infrastructure, and which flows through our everyday lives.”

In Montreal, water is often thought of as abundant and free. In spite or perhaps because of this, residents often pay little attention to it. The Montreal Waterways project aims to reconnect Montreal with its water. To us, water is a fascinating topic that connects the past with the future and the environment with infrastructure, and which flows through our everyday lives.

In an attempt to bring ethnography closer to home, Montreal Waterways conducts ethnographic research into various “water objects” that make up the city’s past, present, and future. Although we hope to touch on a variety of topics as the project progresses, we are currently focused on two such objects: The Big Flush (a political event surrounding the dumping of raw sewage into the St-Lawrence river in 2015) and the history of the St-Pierre River, which was buried and turned into sewage and drainage infrastructure over the past 150 years.

Île Sainte-Thérèse Project: How to tell the story of an island?

In the fall of 2021, mayors from the Greater Montreal area officially announced a plan to develop Île-Sainte-Thérèse (Sainte-Thérèse Island) into an Eco-Park. The park project is an expansion of an already existing network of park and recreational infrastructure across various municipalities throughout the Hochelaga Archipelago. But the new park project on Île-Sainte-Thérèse, which aims to make land and water more accessible to the public, comes at a cost of 50 family cottages that will be evicted from the island. In the year following this announcement, a group of graduate students from Montreal Waterways, a working group from the Concordia Ethnography Lab, worked collaboratively to explore the island’s history and the material entanglements with land and water, as well as to speculate what is to become of this place and its inhabitants.

While the proposed eco-park and impending eviction are reminiscent of a troubling history concerning National or Provincial Parks as a form of conservation, Île-Sainte-Thérèse offers its own story, albeit a fragmented one involving multiple actors, each with a claim to the island’s landscape and heritage. The group shared and engaged with ethnographic methods and imagery, and brought these fragmented pieces together collectively; they did so not in a way that is definitive, fixed, or complete, but rather to demonstrate how these fragments move—and move us—when telling the story of an island.

Stories of a River and the Story of a Collector and the River it Swallowed

This research project questions how discourses and practices of modernity and development have led to the physical transformations of the Saint-Pierre River, and how these relate to the different material practices, representations, and symbolic nature of the river.

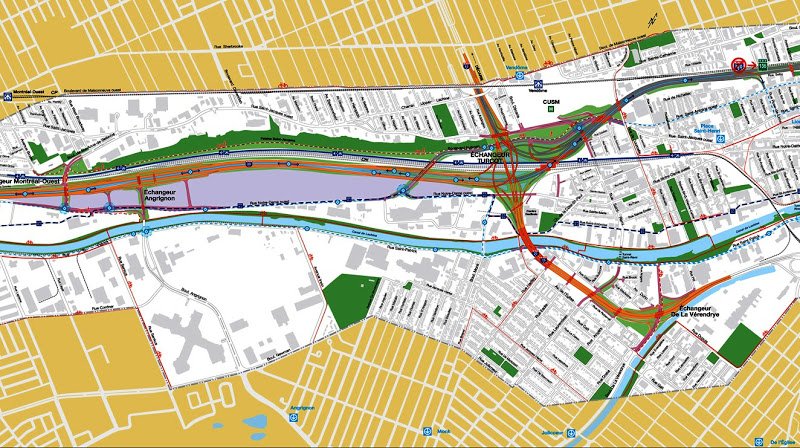

Using historical-geographical materialism methodologies, an ethnographic inquiry into human, non-human and infrastructure actors, and counter mapping we seek to develop a recursive (re)shaping of the water infrastructure that has absorbed and exhausted the Saint-Pierre River. Such methodologies will allow us to identify how infrastructure was used to colonize and lay claim to the area, as well as illustrate alternatives to “the incremental destruction of sustaining habitats” (Aberley, 1993:4). Through the creation of a counter map and ethnography of the river and water infrastructure, we will contest the homogenization of the space as it represented in zoning regulations, land-use maps, and property regimes to offer new means of expressing hydro-social relationships in place.

In considering the material concerns that have come to bear on the construction of infrastructure in Montreal’s southwest area (i.e. the Lachine Canal, the railroads and yards, the Turcot Interchange, etc.), as well as public health and water quality issues we will work to “daylight” the historical policies, decisions, and motivations that have resulted in the burying of the river. The flows of fresh water, sewage, and storm water in urban spaces represent complex arrangements between human and non-human dimensions that challenge us to think about the ways in which policies and everyday practices intersect with the materiality of the world. As an actor within bio-cultural worlds, water infrastructure is in a dynamic interaction with the environment (Lea, 2017) while materializing ideologies and discourses of development, progress and modernity.

A Moment of Infrastructural Visibility and Eventfulness

This research group takes a deep look at the event of The Big Flush of November 2015 where the Montreal Municipal government dumped 8 billion litres of raw sewage into the Saint Lawrence River in order to accommodate the renovation of the city’s sewage lines. The dump was supposed to be a mundane event, given that sewage dumps like this one are common infrastructural practice. However, as news of the dump circulated and it became a matter of intense public contention, the event became interesting for its infrastructural and environmental consequences, its display of “infrastructural visibility,” and its participation in a political theatre that pitted then-mayor Denis Coderre against various political actors.

When it turned into such a highly contested event, The Big Flush made visible different and unequal relationships to water and sewage infrastructure in Montreal. In order to untangle the intricacies of the event, this group asks two main questions. First, how did The Big Flush become a matter of political concern? Second, what does The Big Flush tell us about the potentials of infrastructural politics?

To answer these questions we explore the media coverage of the event, both the way in which the story circulated and how the coverage made visible the functioning of the infrastructure.

We also conducted interviews with various (overlapping) groups including activists, bureaucrats and civil servants, indigenous communities, politicians, and engineers and other experts. We hope to uncover what it was about this moment specifically that created such heated public debate. We also explored actions (or inactions) that took place around sewage infrastructure in Montreal since the event with an eye to what activists and politicians have pursued.

We explore opposing narratives that surround the event, such as the conflicting claims made by experts and politicians in terms of the environmental impact the sewage would have on the river and surrounding ecosystem, and consider whether the event was a failure or a success.

There’s Always the Other Side

There’s Always the Other Side is an ethnographic film written in 2018 by Treva Michelle Legassie in collaboration with Alejandra Melian-Morse, Alix Johnson, Marie-Eve Drouin-Gagné, and Élie Jalbert

It is a three minute short film documenting traces from a research trip with the Waterways research group to the Jean R. Marcotte water treatment plant in Montreal. The film is an assemblage of audio, video, and written documentation captured by Legassie and others during the research trip.

There’s Always the Other Side takes a sensing and an immersive intuitive approach to researching and capturing a site. Overlaying inputs from multiple channels of documentation (audio recording, cell phone photography, a DSLR camera, and a go pro shot in tandem by Legassie on site), the video work offers a multichannel audio-visual capture. The voices present field note recordings from members of the Waterways research group to document the individual experiences of Alix, Marie-Eve, and Élie during the research trip.

In an attempt to rethink methodological approaches to anthropology (specifically ethnography) by making work with visual and auditory “field notes,” There’s Always the Other Side becomes a collage of research-turned-creation.